From Marine Yard to

Quality Waterfont Living

Old Tanjong Katong is most significant for its origin and growth as the “marine yard” identified in the Raffles Town Plan of 1826, and its role in Singapore’s subsequent development into the global maritime hub it is today.

The Past

Old Tanjong Katong, which means Turtle Point, spans Upper East Coast Road and Tanjong Rhu.[1] The idyllic coastal area was designated a marine yard by the British in the 1820s. [2] A sizeable Malay community had settled there around the same time, following pressure by the administration to vacate their now prime land near the Singapore River. [3] By the 1860s, it had developed into an area attracting the wealthy for their luxurious seaside residences. [4]

It was mapped in 1822 by Captain James Franklin as Bugis Town,[5] and appeared as Sandy Point in the Raffles’ Town Plan prepared by Philip Jackson in 1828.[6] It is unknown when the name ‘Tanjong Rhu’ came into use, but the area has been referred to as such since the early 17th century, being labelled “Tanjon Ru” in Emanuel Godinho de Erédia’s 1604 map featuring Singapore.[7]

Figure 1: (Left) Bugis Town, Capt James Franklin[8]; (Right) 1604 Map of Singapore[9]

Singapore’s strategic geographical location, at a crossroads of important trade lines[10] linking the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean perfectly positioned it as a meeting point and for the restocking of goods. Groups that used Singapore for this included Buginese on their way to Mecca and traders travelling between the west coast of North America or China to the Indian continent and the Middle East. It was also naturally a good place to make necessary repair work to their ships before journeying on.

The first few shipbuilders on the site included William Flint, who started his company there in 1822. [11] Also notable are George Lyons and his brother who set up their shipbuilding yard there in the 1850s.[12] Others soon followed, including Thornycroft and United Engineers. [13] By the early 20th century, Tanjong Rhu had become known for its shipyards.[14] Vessels built and repaired at the Tanjong Rhu shipyards were of various sizes, including high-speed patrol boats, warships, launches, tankers and tugboats. [15] Clients included local sources such as the Singapore Marine Police Force and government-linked agencies abroad such as the Ceylon Navy. [16]

In the 1940s, during the World War, Thornycroft’s shipyard was taken over by the Japanese and was severely damaged. [17] When the war ended, Thornycroft regained possession of the shipyard and took several years to restore the shipyard to its former condition. [18] In January 1968, Vosper Thornycroft Uniteers, as the company was later known, opened a $1.5 million administrative building and boatyards at Tanjong Rhu. [19] In addition to being home to shipbuilding businesses, the Bugis fleet coming from the Celebes, now Sulawesi, also anchored at the Kallang Basin by Tanjong Rhu during the 19th and early 20th centuries for trade. [20] The Bugis fleet continued to dock at Kallang Basin until as late as the early 1960s, after which they started to anchor off Telok Ayer Basin instead. [21]

Figure 2: Guide Map, Singapore Town[22]

The ship building/repair during those early days at Tanjong Rhu/Kallang River has been well-documented – both in published as well as in digitized form -- in scholarly works including The Sea Nomads by David Sopher. A rich history of the early Kallang River Basin are also available in local publications such as Our Home by the Kallang River : Past, Present and Future by Sue-Ann Chai et. al. A large collection of old pictures are also available at the National Archives of Singapore. While memories and the senses like the smell of burning fuels from ship-repair and charcoals along the high polluted Kallang River are no longer with us, many Singaporeans could still remember and recall the neighbourhood fondly to these days.

The Present

Post-Modern Narrative

In the present day, Singapore has continued to grow from strength to strength as a world-class player in the marine industry, with increasingly international clientele. Its services include ship repair, shipbuilding, rig-building and offshore engineering, coupled with other marine supporting services.[26] Ship repair and conversion remain the backbone of the industry, accounting for more than half of the total revenue.[27] The industry on a whole plays a crucial part in Singapore’s economic growth, generating a turnover of close to $10 billion and employing 100,000 workers.[28]

While Singapore is still well-known for its maritime industry, its associated activities are now mostly centralized in Jurong. No physical traces of Tanjong Rhu’s shipbuilding roots remain in the area, with it being taken over by multiple sprawling condominium complexes since the rezoning of the area for residential use in 1983. The much-loved residential district pioneered up-market waterfront living, a novel concept to the Singapore of the 1980s.[29] It is still valued for its safety and tranquillity, though the loss of its shipbuilding roots is acutely felt, with road names the only reminders of the area’s industrial past.

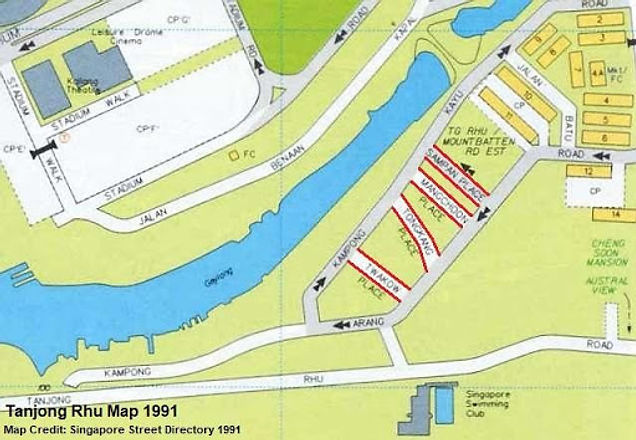

Figure 3: Tanjong Rhu Map 1991 [30]

Of the four roads named after boats of significance, only Sampan Place remains. There are also Kampong Kayu Road and Kampong Arang Road which adjoin Tanjong Rhu Road and refer to wood and charcoal respectively.[31] Also notable is Jalan Benaan Kapal, meaning ship building road, which is situated on the northern shore of Geylang River.[32]

Evolution of the URA Master Plan (1958 - 2019)

In the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA)’s Master Plan 1958, the long sand bar of Tanjong Rhu is designated for industrial use. This extended on both sides of the coast, and further up Geylang River, which was used for the associated industries of timber and charcoal.

Figure 4: URA Masterplan 1958 (Areas for industrial use in purple) [33]

A major ten-year-long government-led clean-up of the Kallang River Basin was initiated in 1977 in response to its state of pollution.[34] Industrial activities were seen to be a major source of debris and flotsam.[35] Resistance to government plans to relocate the lighterage industry to Pair Panjang gave way in the face of political will and urgency.[36] The shipyards were identified as another cause of the pollution. However, this time resistance to their removal came from the government’s own Economic Development Board, which held that their relocation would harm their continued profitability.[37] Instead, mergers were encouraged to pool funding for anti-pollution measures.[38] This was highly unpopular with the businesses, which saw consolidation imposing unnecessary operational costs detrimental to the already floundering industry.[39]

The construction of the 1.8km-long Benjamin Sheares Bridge and the East Coast Parkway (ECP) on reclaimed land served to facilitate direct access from the Shenton Way financial district to Changi Airport in the east.[40] However, land reclamation moved the coast further outshore and narrowed ship access to the Kallang Basin.

Figure 5: URA Master Plan 1980 [40] (Areas for industrial use in purple)

The URA’s 1980 Master Plan shows the upper bank of the sand bar still zoned for industrial use. The lower half has been subsumed by land reclamation for construction of the ECP. The restriction of industrial activities to the northern edge of the sand spit and the narrowing of the Kallang Basin due to land reclamation, coupled with the desire to maintain the cleanliness of its waters, the fate of the ship building industry there was all but sealed, with the later redesignation of the land previously occupied by the industry to residential use in 1983.

Figure 6: Tanjong Rhu Before Redevelopment [41]

In the early 1980s, the floundering industrial climate at Tanjong Rhu saw many shipbuilding companies merged, moved out or closed down.[42] Squatters moved into the empty plots, and contributed to the untidy sprawl.[43]

"The maritime origins of Tanjong Rhu are still celebrated as unique selling points.

These help to keep the district’s history in the public consciousness."

In the early 1980s, the floundering industrial climate at Tanjong Rhu saw many shipbuilding companies merged, moved out or closed down.[42] Squatters moved into the empty plots, and contributed to the untidy sprawl.[43]

With the departure of the last holdovers, land reclamation was carried out to even out the bank to prepare it for its residential future. The maritime origins of Tanjong Rhu are still celebrated as unique selling points by developers of the condominium complexes in the area, with maritime-related terms also referenced in the naming of the condominiums themselves. These help to keep the district’s history in the public consciousness.

Figure 7: URA Masterplan 2019 (Areas for residential use in tan) [48]

While the area is now almost entirely residential, there are, however, opportunities to raise people’s awareness of the area’s past, through the potential erection of more heritage markers and creation of heritage trails. Furthermore, strengthening the narrative on Singapore’s shipbuilding past has the potential to grant further legitimacy and international recognition to Singapore’s shipbuilding and maritime activities in the present day. Instilling pride in the hearts of Singapore’s maritime workforce and Singaporeans at large can lead to more Singaporeans seeing the significance of and supporting or joining the industry.

With the passing of the generations that personally witnessed Tanjong Rhu’s maritime industry in its heyday, Singapore risks losing a unique part of its shared heritage, with the remaining names losing their significance if action is not taken to revitalise and engage the public

The Future

What's next for Tanjong Rhu?

From its start as a British trading post in the early 19th century and its subsequent development into the global transhipment hub it is today, the growth of Singapore’s port has been synonymous with the modern history of the island city-state, and the foresight of its early leaders. [49]

While Singapore’s ship repair and building industry no longer operates out of Tanjong Rhu, and indeed, no architectural remnants remain visible today, it has been, nevertheless, a precursor to what Singapore is to be today, a global hub port. The decision taken in 1969 to build Singapore’s first container terminal in Tanjong Pagar propelled Singapore even higher into the global league.[50] Singapore was the first South-east Asian nation with a container port, which has since expanded to become one of the busiest and most connected in the world, with links to more than 600 ports across 120 countries.[51] Every year, more than 130,000 ships call at Singapore, which handles up to 900 thousand tonnes of cargo.[52] This translates into a significant number of up to 170,000 jobs in the shipping repair and building industry in Singapore today.[53]

The continued development and resilience of Singapore’s shipbuilding and repair industry to serve the region and beyond exemplifies the narrative of the Singapore Story. Its birthplace in Tanjong Rhu can thus be seen as the cradle of Singapore’s success. Even though the site has now found a new significance as a much-loved residential district that is safe and tranquil, its roots should not be forgotten as they hold stories and learning points for the future generations to come.

Bibliography

[1] National Heritage Board Singapore, A Malay Kampong in Tanjong Katong, Roots, https://www.roots.gov.sg/Collection-Landing/listing/1071937, Accessed 29 March 2021

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid

[5] Singapura Stories, Bugis and Makassarese Architecture and Urban Neighbourhoods in Singapore, Singapura Stories, 01 October 2017, http://singapurastories.com/2017/10/bugis-and-makassarese-architecture-and-urban-neighbourhoods-in-singapore/, Accessed 29 March 2021

[6] Tan, Bonny, Raffles Town Plan (Jackson Plan), Singapore Infopedia, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_658_2005-01-07.html, Accessed 29 March 2021

[7] Thulaja, Naidu Ratnala, Tanjong Rhu Road, Singapore Infopedia, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_658_2005-01-07.html, Accessed 29 March 2021

[8] Singapura Stories, From ‘Kampong’ to ‘Compound’: Retracing the forgotten connections, Singapura Stories – From ‘Kampong’ to ‘Compound’: Retracing the forgotten connections, Accessed 29 March 2021

[9] De Erédia, E, G, 1604 Map featuring Singapore, https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/eredia.html, Accessed 29 March 2021

[10] Li, C, Connecting to the World: Singapore as a Hub Port, Civil Service College Singapore, 6 Jul 2018, https://www.csc.gov.sg/articles/connecting-to-the-world-singapore-as-a-hub-port, Accessed 29 March 2021

[11] Thulaja, Naidu Ratnala, Tanjong Rhu Road, Singapore Infopedia, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_658_2005-01-07.html, Accessed 29 March 2021

[12] Ibid

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid

[15] Ibid

[16] Ibid

[17] Thulaja, Naidu Ratnala, Tanjong Rhu Road, Singapore Infopedia, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_658_2005-01-07.html, Accessed 29 March 2021

[18] Ibid

[19] Ibid

[20] Ibid

[21] Ibid

[22] D'Aranjo, B. E, The Stranger's Guide to Singapore ... With maps, Sirangoon Press, 1890, https://www.flickr.com/photos/britishlibrary/11205001823/

[23] Vintage Maps and Prints, Old Map of Singapore 1913 Vintage Map

https://www.vintage-maps-prints.com/products/old-map-of-singapore-1913, Accessed 29 March 2021

[24] Harios, Map of Singapore to India, Maps of the World, 2016, https://themapspro.blogspot.com/2016/12/map-of-singapore-to-india.html, Accessed 29 March 2021

[25] British Royal Air Force, Singapore Photomap Tanjong Rhu, 1950, National Archives Singapore, https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/maps_building_plans/record-details/f8cb44e8-115c-11e3-83d5-0050568939ad, Accessed 29 March 2021

[26] ASMI, A Closer Look At The Marine Industry, Association of Singapore Marine Industries, 2018, http://www.asmi.com/index.cfm?GPID=29, Accessed 29 March 2021

[27] Ibid

[28] Ibid

[29] Ibid

[30] Koh, L, K, The Urban Renewal of Tanjong Rhu, ScholarBank@NUS Repository, 1996, https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/184932, Accessed 29 March 2021

[31] Remember Singapore, Jalan Benaan Kapal – A Forgotten Chapter in the History of Singapore’s Ship Repair Industry, Remember Singapore, September 2020, https://remembersingapore.org/2020/09/07/jalan-benaan-kapal-shipyards-history/, Accessed 29 March 2021

[32] Ibid

[33] URA, Republic of Singapore - Master Plan 1958, https://www.ura.gov.sg/dc/mp58/mp58map_index.htm, Accessed 29 March 2021

[34] Koh, L, K, The Urban Renewal of Tanjong Rhu, ScholarBank@NUS Repository, 1996, https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/184932, Accessed 29 March 2021

[35] Ibid

[36] Ibid

[37] Ibid

[38] Ibid

[39] Ibid

[40] URA, Republic of Singapore - Master Plan 1980, https://www.ura.gov.sg/dc/mp80/mp80map_index.htm, Accessed 29 March 2021

[41] Koh, L, K, The Urban Renewal of Tanjong Rhu, ScholarBank@NUS Repository, 1996, https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/184932, Accessed 29 March 2021

[42] Ibid

[43] Ibid

[44] Ibid

[45] Koon Holdings Limited, Marina Bay & Tanjong Rhu Reclamation Works,

http://koon.com.sg/icce-project-marina-bay.html, Accessed 29 March 2021

[46] Ministry of Information and the Arts, Benjamin Sheares Bridge, East Coast Parkway 1980s, Remember Singapore, https://remembersingapore.org/2018/04/29/singapore-expressways-history/, Accessed 29 March 2021

[47] Google, Tanjong Rhu Area, Google Maps, https://www.google.com/maps/place/Tanjong+Rhu/@1.301139,103.8642017,3626m/data=!3m2!1e3!4b1!4m5!3m4!1s0x31da1844bc0d714d:0x7fc00e6a5f05e809!8m2!3d1.2975725!4d103.8770958, Accessed 29 March 2021

[48] URA, Republic of Singapore Master Plan 2019, URA SPACE, https://www.ura.gov.sg/maps/, Accessed 29 March 2021

[49] Li, C, Connecting to the World: Singapore as a Hub Port, Civil Service College Singapore, 6 Jul 2018, https://www.csc.gov.sg/articles/connecting-to-the-world-singapore-as-a-hub-port, Accessed 29 March 2021

[50] Ibid

[51] Ibid

[52] Ibid

[53] Ibid